Space Quest

Space Quest

“And The Cold Stars Glittered On The Corpse Of A Dream”

BTW, does anyone know of an editor plugin for WordPress where you can just have a bunch of google fonts in the font dropdown, and other cool stuff that makes it more like a WYSIWYG system, so you’re less bound to your template and don’t have to learn CSS?

I’ve spent two weeks working on a wasp queen demon lord inspired by my mother in law, and totally not in the way you’d expect from that sentence, and it’s taking too long — designing high-CR critters in Pathfinder is a friggin’ bear (great, now I want to design a CR 20 bear… maybe a bear kaiju… no! Stop it, Lizard! Focus!) — so I thought I’d take a break. Since, for some reason, both of my copies of Space Quest (First and Second edition) were sitting in the pile of random clutter near my computer, that’s what I’m looking at this week.

Space Quest is a digest-sized space opera RPG released in 1977, so it can also be called “No, the other one.” It’s by Paul Hume, which is a name old schoolers like me know well, and George Nyhen, which isn’t. (A lot of what I cover seems to have that split… “Here’s the early work of someone who is still an active figure in gaming (or who is sorely missed), along with a bunch of folks you never heard from again.”) (I’m also reading a lot of 1920s and 1930s out-of-copyright pulps, and same thing: A mix of writers who later went on to define the genre for decades, and others, treated at the time as equals of those greats-to-be, who didn’t. And I’m digressing again. I do that.)

I will be looking at the first edition. The differences, from the outside, are minor. Second Edition has a slick cover; First Edition, a rough one. Otherwise, the art and descriptive text are identical, as is the page count, though the final page and inside back cover of second edition are covered with errata, while they are blank in the first. (This extra text adds a paragraph or so on “Krang”, aka “Space Karate”. Just thought you’d like to know that.)

Traveller, likewise, was first published in 1977. I do not know which came out first; they would likely have differed by only a few months. It is a perfect example of simultaneous creation. To go off on a favorite tear of mine, the phenomenon of many variants on the same topic appearing concurrently is rarely due to conscious copying and anyone screeching “They stole my idea!” has a dubious knowledge of what an “idea” is worth. (Roughly fuck-all, though it might rise to diddly-squat under the right conditions.) Rather, people who are in the same subcultures, read the same books, watch the same movies, and have the same kind of neural wiring will produce similar outputs from these similar inputs. (Creative types, in general, tend to be rare in the general population and, unless they’re professionals, rare within their own peer groups. As a consequence, we (I am being vain) tend to overestimate our uniqueness. Thus, when we see some other creative type coming up with the same thing we did, instinctively assume they must have somehow stolen it, instead of recognizing that when you train two neural nets on the same data, they will end up very close to each other… not identical, but close.)[1]

“This Is A Large And Confusing Game”

Those are the first words on the first page of rules. In the contest of the time, when “Risk” and “Monopoly” were considered among the leading edge of game complexity, a 110-page digest sized rulebook (thus, 55 or so normal sized pages — less than a typical modern games’ supplement describing dwarven throwing hammers (one-handed; two-handed throwing hammers need their own book)) was probably astounding[2], and the authors wanted to let the readers know up-front what they were getting into.

Following the wargaming tradition out of which RPGs were still forming (remember, in the 1977, D&D was just three years old, and while the genre was rapidly congealing into independence, it was still not wholly split off from its parent), the rules are numbered in sections, so the first section is ‘0100’, with subsections ‘0110’, ‘0120’, and so on. (The game refers to itself as providing rules for “science fiction-fantasy wargaming”.

The text is small and dense, both in typography and information content.

Roll A D30

A good example of how the Burgess Shale era of gaming worked. Instead of forcing tables and rules to work with the available dice, you just assigned probability ranges and then added rules to generate these numbers on other dice. (D30s eventually did exist, of course, along with far more baroque concepts.) At the time this was written, all D20s used the numbers 0-9 twice, so you colored in half the numbers to indicate “high”, leading to lots of arguments over which color was “high”, depending on the needs of the moment. “Yes, blue is high! A 20!” “But you need to roll low for an attribute check, so you fa…” “Did I say blue? I meant red! Red is always high for me! You know that!”

Thus, the rules recommend rolling a D6 and a D20, with 1-2 meaning “1-10”, 3-4 meaning “11-20”, etc. It also recommends the following easy system of rolling a D17(!): Roll percentiles (it explains how to do this with the D20s of the era, too), then divide by 17 and round up. Except… wait a minute… that doesn’t remotely work. That gives you a number between about 1 and 6. Unless they meant to take the remainder? Or something?

Huh. Moving on.

We have a glossary of terms, with a mix of the typical mid-70s SF obsession with the metric system (because we’d all be going metric any day now) and game-specific terms such as “hypermeter”, which is how you measure distances in hyperspace. A typical ship under the “N-Drive” travels 1000 hypermeters (or, a hyperklick… because all the cool kids say ‘klick’ instead of ‘kilometer’) per hour. A hyperklick in n-space is a light year in realspace, and a ship normally travels 10 hk a day… which directly contradicts what it just said about 1 hk/hour, unless the ship can only travel 10 hours a day. (All times are given in GAL-, a prefix meaning “Galactic Standard”… one GAL-day, one GAL-year, and so forth.)

There’s a fair number of entries in the glossary referring to the “20 Suns Combine”, the default setting for the game, but it is important to note that the first paragraph or two makes it clear the target audience for the game is “the growing number of gamers who get off on the creative challenge of building their own campaign”. (And I just noticed that self-same early section notes there are no rules for “the personal scale”, which seems odd since, flipping ahead, I see plenty of rules for normal person-to-person melee and ranged combat. Not sure what they meant there.)

Not Dying During Chargen

There’s a page of tiny type detailing the “History of the Galactic Empire”, and its fall at the hands… or tentacles… or claws… of the Sniz, invaders who appeared from nowhere and sabotaged the great galactic teleportation net, ending the Empire, reducing all to chaos, “And the cold stars glittered on the corpse of a dream.”

God damn, I love that line. Hang on, changing my heading text for this article. There. Done.

0400: Players And Characters

Before we get to character creation, we have to have a reaction chart. This was common back in Ye Olde Dayse. Thinking about it, it was a big part of the transition from the GM as a referee for a wargame to the GM as a storyteller and worldbuilder. It seemed more “fair”, I suspect, for the outcome of a meeting between the PCs and a group of NPCs to be random instead of the result of the GMs judgment as to the likely response. This quickly changed as a body of convention, tropes, and expectation rapidly evolved to set presumed defaults and provide a number of signifiers that could be used to communicate, in the game context, the likely demeanor of an encountered group. (In other words, when the GM describes a group using terms and phrases that indicate ‘a bunch of peaceful merchants’, a set of implied expectations are communicated, vs. terms that indicate ‘a group of bandits’.)

Following the table is advice that the GM should decide when and how this table is to be used; a character seeking information in a bar should not “be attacked for a simple question”, although a low roll “might start a brawl”. (This more-or-less mirrors the modern style of play, where the player role-plays a brief conversation, then makes an appropriate skill check and deals with the consequences.)

0410: Building A Character

There’s a number of steps to take. Step 1: Choose a species.

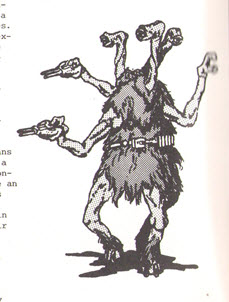

Those hoping for the usual gaggle of space opera races — cat men, bear men, dog men, rat men, snake men, men men — will be disappointed. There are only three races: Humans, Trilax (tri-symmetrical beings with three legs, three arms, and three eyestalks) and silicoids (rock men).

This surprises me. Perhaps it shouldn’t. Traveller had only humans to begin with. (In the earliest printings of Traveller, the Imperium was either not mentioned at all or was a vague reference to a generic background government.) It may be that the literary SF that underpinned the subset of SF fans who were also drawn to roleplaying was strongly humanocentric. At the time, “media” SF fans were considered an unwelcome and dubious intrusion into fandom, not “real” fans at all. (Remember: When THEY want to keep YOU from participating in THEIR subculture, it’s “gatekeeping” and it’s bad. When YOU want to keep THEM from participating in YOUR subculture, it’s “preventing cultural appropriation”, and it’s good. Got it? Great.)

Anyway, given the rather uninspiring non-human choices (no catgirl space pirates? Dafuq?), I’m going with human.

Abilities are determined by rolling a variable number of 6 sided dice. Humans roll 3d6 for everything. Trilax, by contrast, roll 4d6 for Coordination and 2d6 for Speed.

The abilities are:

- Physical Power

- Coordination

- Speed

- IQ

- Psi

- Empathy

- Vitality

The highest score you can roll is also the Racial Maximum. This can normally not be exceeded by the use of drugs, psionics, or technology, though “the most potent drugs” may temporarily break this limit, and “expensive” Bionic modifications and rare Alien devices might permanently raise your abilities beyond this. Also, the Capitalizations for “Bionic” and “Alien” are As Written, as this Game, like many From this Era, had a Bad Case of Random Capitalization.

Let’s get rolling, shall we?

- Physical Power: 7

- Coordination: 9

- Speed: 8

- IQ: 11

- Psi: 7

- Empathy: 12

- Vitality: 11

And, y’know what? Screw that. Let’s try again.

- Physical Power: 9 (Not off to a good start)

- Coordination: 14 (Better…)

- Speed: 13

- IQ: 16 (!)

- Psi: 6 (And we’re back to normal.)

- Empathy: 13

- Vitality: 10

OK, that’s playable, at least.

(And this, kiddies, is why games rapidly evolved to “best 3 out of 4”, or point-based systems.)

Physical Power is my strength. It’s modified based on my homeworld’s gravity vs. the current gravity to produce Effective Power. My native gravity is rolled on a table on the next page. I rolled an 8 on a D10, which per the chart, puts me on a 2g world. My Effective Power is Physical Power x (native g/current g). On a 1 g world, it would be 18. I can lift 10kg per point of Effective Power, or 180 kg, maximum. At 50% of that, I suffer a -4 to Speed and Coordination, and at 75%, this increases to -6.

Coordination is dexterity.

Speed determine how many actions I can take, and if I’m of the Spacer class, it gives me bonuses to my use of a spaceship. If I’m a Warrior, it gives me some dodging abilities. And it gets more complex, because there is also the Effective Speed, ala Effective Power, with the same formula. On a 1g world, my Effective Speed is 26(!), and I can perform 4 actions per mt. “Mt” is “Melee Turn”, of course. However, if we’re in zero g, we use base speed, not effective speed, and we use the “0 g Result” column of Table 0443.1. No, I’m not kidding about that… it’s really Table 0443.1.

“Actions” are “simple actions” such as hitting someone, moving, shooting, and so on… a fairly common understanding now, but in need of explanation then. (Hell, we still get into arguments about exactly what can be done in a single melee round… ) The speed table does not apply for actions that would take longer than one mt, and the GM is tasked with deciding what that means.

I’m not sure I like the idea of gravity affecting speed when it comes to actions/round. Sure, I might run faster in low gravity, but could I really pull a trigger faster? I’d use Coordination (unadjusted by gravity) for action speed, and Speed for just… speed. Running. That kind of thing.

Oh, and Spacers get to add their speed to their “GO-rigger Bonus”, a term “which will be explained in detail later in the rules”. And, yes, Warriors get a defensive bonus due to their Effective Speed.

Thus far in the rules, those from high-g worlds have significant bonuses and no drawbacks.

IQ: IQ is not raw intelligence in Space Quest, but measures “affinity for technological devices and activities”. Due to eugenics and “advanced medical techniques”, no severely dain-bramaged people exist in the Combine, and “a character is only as smart as the player who controls him”.

For most purposes, IQ divides into three levels: 2-5 allows you to use “pushbutton” devices only, without the ability to repair anything or use unusual or alien technology. 6-11 lets you use all common devices and alien tech if you’re shown how, and make some simple repairs. 12+ lets you study alien devices to figure out how they work, and grants access to the “Technic” class. And, by the way, Technics with a high IQ gives a “POWER-rigger” bonus, if you’re a Technic who is also the ship’s engineer. At 16, I can add 2d6 ERG to the engines when the captain yells “Dammit, Scotty, I need more power!” “I’m rollin’ all the dice I can, Cap’n! I can’t roll a 13 on 2d6!”

PSI : Psionic power. This is key for “mutates”. Mutates (a class) have “active” psi, while the rest of the slobs have “latent” psi. With my Psi of 6, I don’t think “Mutate” is the class for me.

Empathy: This affects reaction rolls; see above. Curiously, it’s not affected by gravity or class.

Vitality: This measures “general resistance to physical hardships or damage”, and is instrumental in determining your hit points, which are Vitality * 2 + 1d6, which, for me, is 22.

Surprising no one who is familiar with mid-70s design patterns, you gain hit points as you go up in level based on your class. Warrior +2d6, Spacers and Technics +1d10, and Mutates and Biotechs +1d6.

Next we get into gravity, including Table 0448.2: GRAVITY ABREACTION TABLE, and I think that’s a good stopping point. I’d honestly expected to get the entire thing done in one go, but it was not to be.

PS: “Abreaction” is a perfectly cromulent word.

[1]I find myself often splitting the difference on the “great man” theory of history vs. the “historical inevitability” theory. Both are trueish. If you went back in time and assassinated Columbus, you’d delay the European arrival in the Americas by a few years to a few decades, at most. Too many factors were pushing the need to find an alternate route to the trading ports of Asia and India. Any scientist or inventor builds on preexisting knowledge that is widely known within their communities, as well as seeing the same problems to be solved or needs to be filled[1a]. At the same time, it doesn’t matter how many people might have found something, done something, created something… praise and honor is due to the first one to actually do it, to be the first to put the pieces together.

[1a]And this, in turn, is why any variant on the meme of “Some guy in East Bumfuck, North Dakota, invented a car engine that gets a thousand miles to the gallon but Big Oil shut him up.” is bullshit, along with any kind of scam for “cheap fusion” or other forms of “free energy” where the creator never releases his models and prototypes for testing under controlled conditions (meaning, he is not there to rig things), or files patents showing how their design works, because they fear “someone will steal my secrets!” If some miracle power source exists, and they found it, someone else, having access to all the same underlying knowledge, will do it, too. You can’t suppress the laws of physics. Anything that can be discovered once can be discovered again.

[2]And to invoke another boilerplate rant… certain advocates of Old School Revisionism point to the “short” rulebooks of the 70s and 80s (32 to 128 pages) and talk about how “simplicity” was a design goal of the era. No. No, it was not, with a tiny handful of exceptions (Tunnels & Trolls being one). At the time, these games were hideously complex. Terrifying. Intimidating to “mundanes”. And we, the players of the era, loved that. We (being nerds) enjoyed the challenge of mastering such complex systems when our non-nerd associates were overwhelmed by anything more advanced than Candyland. The length of the rulebooks was due to the economics of the age (printing was far more expensive, and the actual work of writing the rules was much more labor intensive, involving typewriters, literally pasting in artwork, retyping the rules if anything major needed to be changed, hand-assembling a table of contents by writing it after the layout was done and you knew what page things went on, ad infinitum), rather than an ideological commitment to “simple rules”. Subsystems to cover many actions weren’t omitted due to a belief “you don’t need rules for that”; they were omitted due to the fact there wasn’t room.

Something like this?

https://wordpress.org/plugins/wp-editor-widget/

Pingback:Space Quest II | Lizard's Gaming and Geekery Site