Dragon Tree Book Of The Dead

Dragon Tree Book Of The Dead

Because I Haven’t Posted In A While

And This Was By My Desk

OK, today, and for the foreseeable future (“The problem with foreseeing the future is that it hasn’t happened yet.” (Not Yogi Berra), we’ll be looking at the Dragon Tree line of… erm… sort-of AD&D or OD&D supplements that are also sort of Arduin and also sort of “We were just using our house system and wrote some stuff up”, or, in other words, the typical Burgess Shale Era third-party stuff, except that these are from the 1980s, so it’s more like Lazarus Taxa, things that should have been extinct, but weren’t.

I have several such books, including The Book Of The Dead, the Dragon Tree Spell Book, Monstrous Civilizations of Delos, and Beyond The Sacred Table. That latter one is mostly about LARPing, which is of minimal interest to me, so I may or may not delve into it.

I’m starting with The Book Of The Dead for absolutely no reason. It was on top. It’s also how I pick out clothes to wear. What can I say? I’m not one of the world’s deep thinkers.

Note: These books are square bound, fragile, and hard to replace. So I either squish them on my scanner (and risk breaking the old, dry, binding), or take pictures w/my cell phone. Thus, the images are going to be of highly dubious quality, just like my writing. At least there’s parity.

For the record, this is the first edition, published 1986. I do not know if there was a second edition.

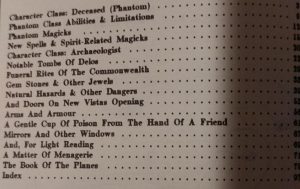

Anyway, let’s take a look at the table of contents. As we’ve come to expect from a certain style of old-school supplements, it’s a carefully organized and logical document where everything flows naturally from one topic to another and I actually managed to type that without laughing too much. Go me! As usual, it’s a melange of topics scattered one after the other. There’s a slightly archaic, pseudo-scholarly

New Class, Spells, Cantrips, Other New Class, Gems, Poisons, Monsters… This Is Old School Organization.

tone to both the chapter titles and the writing, less personal than Hargrave’s or early Gygax, but still with a distinct voice, something that was starting to fade from the Big Corporate Games (yeah, like TSR was ever more than a flyspec in corporate terms), or would be taken to gross excess in the upcoming wave of 90s grimdark very very very serious games. (“Place thine Orbs Of Chaos into the Alignment Of Conflict to determine if the Saga of Discovery you are undertaking shall grant you the Power Of Choosing The Course of Battle”, or, in other words, “Roll for initiative.”)

It should also be noted the print is very tiny and the headings are written using a pseudo-calligraphic font that blurs together when printed. They were clearly going for a higher level of typographic professionalism than the fixed-width typewriter style of older books, but it ended up being less usable.

You’re Dead! What Do You Do Next?

Despite “revolving door afterlife” having been a running joke before this book was written, the authors write as if PC death is, in general, permanent… they do mention Raise Dead and similar, but there’s a tone/attitude that this is generally rare rather than expected. I might be reading too much into this, or it might be part and parcel of the nature of “West Coast” gaming, to the extent such regional styles still mattered by the mid-80s.

Anyway, the introduction to “Character Class: Deceased” begins by commenting that those who die during great quests might not be content to merely shuffle of this mortal coil.

This being old-school (late old-school, I suppose. Very early Triassic?), we start with a complex set of rules[1] for determining if a character can return from “the Plane of Shadow”. (This usage may predate its first use in AD&D… not sure, and I don’t want to get sidetracked by looking. I started writing this a week ago and just got back to it now.) Time and manner of death both impact this. The more traumatic the death, the better the odds of return. A swift, painless, death may leave a lust for vengeance, but it’s so quick there’s less chance of coming back.

Anyway, the rules. These are mixed into long paragraphs of teeny tiny type. This is not a bad thing, as there are several examples and a discussion of why the particular rules exist, within the framework of the Book of the Dead’s view of the afterlife. This gives a GM the tools needed to better adjudicate situations not covered.

You start with adding together Intelligence, Wisdom, your Prime Attribute, and your level. (Multiclass characters add their highest level and one Prime Attribute. I’d have averaged them. House rule!) This totals to your Ego Strength, which is capped at 75%.

Now, you can only return within three days. On the first day, it’s a fixed percentile check on Ego Strength.

On the second day, you roll against 2/3rd of your Ego Strength.

On the third day… yup, roll against 1/3rd.

Boy, if Jesus had crapped out on that final roll, the world would be a different place!

But you’re not dead… er… undead… yet! This roll just determines if you manage to hold on to your memories and motivations after experiencing death trauma. It doesn’t mean you actually come back!

Slow And Painful Wins The Rez!

(That’s “Resurrection” For You Non-MMO’ers)

If your death was slow, including lingering wounds, starvation, slow poison, etc., you gain a 10% boost to Ego Strength, raising the max to 85%.

But! A slow death also decreases the motivation to return, giving a -20% on your roll to actually come back. This penalty is due to having time to prepare, to pass on information, undergo last rites, etc., which may be appropriate in some cases and not others. Someone starving alone on a mountaintop might have time to psychically steel themselves for death, but they will still have plenty of “unfinished business”. As a GM, I’d be really flexible with these numbers. Again, the fact the rules explained the “why” of the modifier instead of just presenting it as a fait accompli is helpful.

A sudden death, on the other hand, adds 10% to the motivation to return.

Now, on to type of death.

Someone who “died as they lived”, in accordance with their goals and dreams, is less likely to return than someone who perished with much undone. An example is given of a mercenary who dies in battle (in which he did well, other than, you know, dying), and whose faith says that a death in battle is glorious and will earn him a well-deserved reward, and of a priest who got killed mid-quest and whose companions are now without his aid.

The first is given a -10% modifier, while the Priest gets +30%, in three 10% chunks: +10% for the quest, +10% for protecting the party, and +10% because such protection is his assigned task. This formulation is called the Dumbledore System, where endless rewards are arbitrarily handed down, because he’s in charge, dammit.

Both get +10% for sudden death, so the merc is at a flat 0% and the priest is as 40%.

In The Unsure And Uncertain Hope Of Resurrection

If you expect to be brought back through formal spells, you have a reduced chance of self-revival, because you’ll be chillin’ on the spirit plane waiting for someone to cast a spell. This imposes a -50% penalty. Neither of our example characters expected anyone to fork out to bring them back, so their numbers remain as-is.

Next, do the characters (not their players) want to return? Our mercenary has no real motivation to come back as a phantom when he died well and sees a glorious reward ahead, but the priest petitions his deity for a chance to (partially) complete their work. He is granted a +20% bonus to motivation. The rules note this value is very flexible and encourages the GM to set an appropriate value.

Returning as a phantom is temporary and limited. The character returns as a shade based on their motivation and is there to fulfill a purpose. They can’t just go off and have ghost adventures. This is a mechanic that allows a player to continue… sort of… until the conclusion of an adventure, without the awkwardness of introducing a random new PC. (Imagine if when Boromir died, his younger brother just showed up in the story and started interacting with some hobbits and Gandalf! But as ridiculous as that contrivance would be in a novel, it’s a totally accepted part of RPGing!)

(I’d note this treatment of a character as more than a token used by a player is a sign of the transition from the earliest RPGs to what the hobby had mostly morphed into. In Ye Olde Dayse, not only was it perfectly sensible for Gork The Dwarf to be replaced by Vork the Dwarf, there was rarely even a timelag of note. No matter where the party was, Vork would be there by the next significant encounter. Questioning this would be like questioning the use of any random bit of detritus to replace a missing Monopoly token. It just didn’t matter at the time, but by the mid-80s, it was starting to. Hence, these rules.)

The Phantom Menace

I Had To

Sorry

There Is No Roll To Determine If You Are Funky Or Not, And If You Get That Reference, You’re Old And Watched Too Many Cartoons In The 1970s

When you come back as a phantom, you start at first level. You still have access to your old abilities, within limits, but you don’t advance them. Casters can’t use offensive spells, or spells requiring material components, unless they materialize. (A Primary Ability of the Phantom Class).

You get your pre-death hit points, +1d10 per phantom level. Healing damage is complex and difficult.

As a general rule, you can’t directly cause harm to any living being. If you contribute to the death of something, it will return (75% chance) to haunt you!

(This is one of those areas where a lot of GM adjudication is going to be needed and a lot of players will look for loopholes. If you heal someone who then kills something, is that contributing? What if you gather information that allows other players to kill something, but don’t directly participate in the battle?)

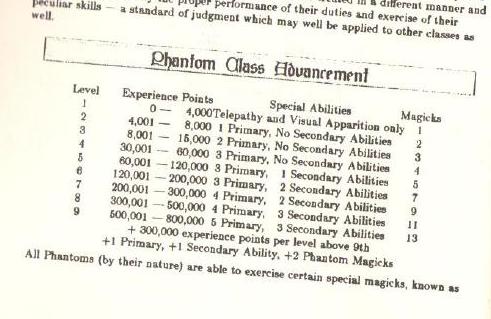

Phantoms gain Primary and Secondary Abilities as they advance. These seem to be innate, at-will powers, except as noted. They also gain “Magicks”, which you know have to be cool, because there’s a “k”!

We will discuss these whenever I get the next part written.

[1] People who were not actually around at the time have the bizarre delusion that “old-school” games were “rules lite”. No. They were, due to budget and technology constraints, short (in terms of page count), and thus, had less space for rules. As soon as space became available (in magazines and supplements) more and more rules were added. There was no inherent game design philosophy of “fewer rules”. That was an emergent property, and one seen as a weakness, not a strength. (I’ll need to double check, but I recall the Dragon article on the “Samurai” class, published sometime in the first two dozen or so issues, had a higher word count than the entire “Men and Magic” book of OD&D! But I digress.)

Pingback:Dragon Tree Book Of The Dead II – Lizard's Gaming and Geekery Site

Pingback:Dragon Tree Book Of The Dead III – Lizard's Gaming and Geekery Site

Pingback:All The Worlds Monster’s Volume 3, Part V – Lizard's Gaming and Geekery Site

Pingback:Dragon Tree Book Of The Dead VI – Lizard's Gaming and Geekery Site

Pingback:Dragon Tree Book Of The Dead VIII – Lizard's Gaming and Geekery Site

Pingback:Dragon Tree Spell Book – Lizard's Gaming and Geekery Site

Pingback:Handbook Of Traps And Tricks – Lizard's Gaming and Geekery Site